I hadn’t thought about it until I read the following comment at the site of National Catholic Reporter’s recent article about the predicted exodus of Anglicans to the Catholic church, following a decision by the Church of England’s General Synod to consecrate women bishops. A commenter notes,

Notice the new fad for bishops, Anglican AND Roman Catholic, to wear their pointy hats tilted back at an angle, rather than straight up? How silly they all look. Women will look silly, too, in mitres.

The comment has to do with the picture at the head of the posting, a snapshot of archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams and Episcopal bishop of New Hampshire Gene Robinson.

And yes, this poster is absolutely right. Now that I think about it, there definitely is a new ecclesial fad for bishops and archbishops to wear their miters at a jaunty angle, pushed back to show, what, that they’re hard-working men who can’t be bothered with sartorial niceties? That they’re regular guys who shove back the brim of their ball caps as they scratch their heads to cipher and think?

I’m not sure.

I only know that, now that the NCR poster has pointed this out, I recognize that this style is everywhere these days:

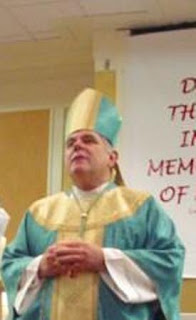

With the new archbishop of Miami, Thomas Wenski, a sporting lad who has long preferred the laid-back mitred look that accentuates a bishop’s firm chin . . .

And who, when he’s not sporting a church miter, prefers a natty biker’s helmet echoing his ecclesial rank.

Or take the archbishop of New York, Timothy Dolan, who knows how to work a miter to show it off to full advantage against those tall buildings of his powerful East Coast see . . . .

And, as I look at these pictures, I think that, all things considered, I’m inclined to agree with retired Australian Catholic bishop Geoffrey Robinson (Confronting Power and Sex in the Catholic Church: Reclaiming the Spirit of Jesus [Dublin: Columba, 2007]), who reminds us that the miter originated in the headdress of Graeco-Roman court officials. And so its long use as a symbol of authority in the churches reminds us of a highly ambiguous development in the history of the church, one we might not wish to celebrate so effusively—the merger of church and state with Constantine, a development Augustine sealed with his urging of state officials to coerce Donatists to return to the Catholic fold, to coerce them with violence, if necessary.

As Bishop Robinson—who also has a keen eye for how recent church fashions have been developing, and how they echo ecclesiological developments notes—miters have been growing higher and higher, of late. The mine-is-bigger-than-yours school of miterdom seems to be reaching its limits, with top-heavy miters now inclining precariously at a jaunty angle at the back of reverend heads that seem to be working hard to support their weight.

Bishop Robinson proposes—with eminent sanity—that we might wish to dispense with miters altogether, seeing as how we are a church founded by a Lord who preached that the first must be last, the humble lifted up and the mighty cast down, and leaders must be servants of all and not little lords over their brothers and sisters.

Sadly, I don’t look for anyone in church officialdom to take up Bishop Robinson’s proposal anytime soon. And more’s the pity, when the jaunty high hats tilted back at alarming angles are beginning to look, well, like something from a Monty Python skit about the ministry of silly walks.