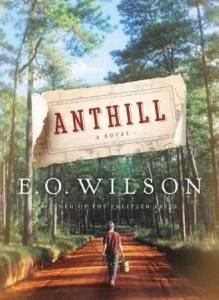

I tried to like E.O. Wilson's novel Anthill (NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2010), which I read while we were traveling last week. I really did. It's a novel whose grand idea--the earth is under siege by humans oblivious to the consequences of our reckless misuse of creation--needs desperately to be liked.

But, in the end, I found the novel irritatingly didactic. It reminded me of why I avoided like the plague the grim earnest tutelary works of American literature when I studied English, and went instead for British writers, with their lighter touch, delicate sense of irony, and ability to fathom the way in which a whole world rises and falls on a word said here, a conversation casually unfolding there.

Anthill contains some splendid passages, particularly as the action heats up and the protagonist Raphael Semmes "Raff" Cody discovers that, in his attempt to save a tract of virgin forest and bucolic wild land in south Alabama, he's up against a deadly cabal of community "developers" (including his uncle) intent on enriching themselves while pretending they're all about Alabama first and last, Alabama always, and demi-monde O'Connoresque preachers like the Rev. Wayne LeBow, who are actively promoting the demise of the world as a prelude to the rapture, to their rapture. LeBow, who tells Raff the following:

God didn't send His only Son to save bugs and snakes. He sent him to save souls. God doesn't give a shit about the land and the creatures on them except how his people can use them. This is just a place on the way to heaven or hell. Anything that's against His will is the devil's work.

And that's a passage that rings all too true as a description of where broad swathes of the American public are now when it comes to concern for the environment and the role of religion in promoting or inhibiting that concern. It's a passage that rang true as I read it days after the media of an entire nation had just chronicled yet another spasm of the rapture hysteria for which American culture has come to be known around the globe. Wilson's analysis of how self-interested corporatists who claim to scorn the crude religious ideas of lower-class evangelicals actually collude with that group in keeping Americans scientifically and environmentally ignorant provides valuable insight into precisely why the mainstream media continue to fixate on the pronouncements of the Rev. Harold Campings of the world, while pretending to poke fun at such pronouncements.

It's all about the money, don't you know. It's all about business. Because that's what truly makes the world (and the media) go 'round.

The preceding passage also rings true as I read in the blogs of leading Catholic journals in the U.S. comments by many readers who more or less agree with the Rev. Wayne LeBow in his assessment of the fundamental message of Jesus: it's about the soul. The body doesn't count. This world is just a staging ground for heaven or hell.

And concerned Catholics should agree with the Vatican that doling out food to hungry folks or healing the sick isn't really about their bodies but about their souls. It's not about following Jesus's command to minister to him in the least among us. It's about remaining Catholic and making sure hungry folks know that the loaf of bread they've just received comes with a Catholic stamp of approval. Not an Anglican or a Baptist one.

It's all about saving souls (and all about business). And it's all about making sure that the designated soul savers--men, of course, and in the Catholic system, the celibate, ordained men at the top of the heap--remain in place as essential cogs in the wheel that empowers the machinery of salvation anywhere that machinery grinds. Wilson skewers the dangerous pretensions of these childish soteriological notions that fire the hearts and minds of far too many people around the world very well, and his book is worth the read for these passages alone.

Still. There's this: there's the fact that the book's plot is essentially a story about Men Doing Things. Men doing things to each other. Men doing things to women. Men doing things to the world. Upper-class men in banks and lawyers' offices. Lower-class men in honky-tonks and machine shops. Upper-class men meeting lower class men as Men Hunt and Men Fish.

Heterosexual men, to be sure. The only time the story line flirts exotically with the idea that gay folks might exist in this overweeningly male world is when Raff falls briefly and disastrously for wild child JoLane Simpson from Fayetteville, Arkansas. Who has the kind of wild associates and wild ideas one would expect in a callow backwoods girl who imagines that revolutionary activity is necessary if we're to make a real dent in that collusion of corporatist money and retrogressive religion that thwarts environmental reform in the U.S.

JoLane, in short, knows some wild lesbian-feminist activists. Though she's not one herself.

Ultimately, what disappoints me most about Anthill is that a plot that has the makings of a probing discussion of how Americans have gotten ourselves into such an ecological dead-end, and how we can get ourselves out, turns into a hymn to the wisdom of working within the system to make effective change in the world. Anthill is a hymn to the organizations that men--heterosexual men--want and need to make things work well for them in a world constructed by and for men.

It's a hymn to environmentalists, of course, but also to the National Rifle Association, since hunters are environmentalists par excellence, don't you understand. It's a hymn to Harvard and the school's rich pavonian ceremonies presided over by Larry Summers--and when that noxious buffoon is presented without a scrap of irony in the section of the novel that informs us Harvard is the best thing to come along since sliced bread, I really began to feel like Daniel O'Connell and almost decided to throw Little Nell out the train window.

Anthill is a didactic sermon lauding the virtues of working within the system to address the well-nigh intractable problems the human community faces as it faces the fire next time, which we have brought on ourselves in this long, hot summer preceded by killing storms and killing floods through our lust for riches and power, our lust to control and not to understand and live with.

Through our macho assurance that we and we alone are the saviors of the world, and that salvation consists in so ordering the universe that men--heterosexual men, business men, Larry Summers and Rev. Harold Camping (and the pope)--remain predictably and necessarily on top, while women remain in their subordinate places as mothers and helpmeets, secretaries and cheerleaders for Men Doing Things. It's a novel that asks us to believe that the best solution we have to our current ecological crisis--to the fire next time, which is already upon us--lies in Harvard-trained lawyers working within the system to make environmental concern a win-win for Men Who Develop Things and become rich in the process.

And, ultimately, I find this message hard to swallow. But then, I am an Arkansas wild child (if not a mountain-born one) whose mother happened to be a Simpson. For my money--and as a wild child from the backwoods, I have very little of it, and therefore little say in arranging much of anything in the world--our salvation lies elsewhere. Whatever salvation is and however it finds us, I expect it to come from outside our current systems of power and control. And decidedly from outside the male-dominated systems that dole out bread and bits of salvation in the world as it's now made.

No comments:

Post a Comment